The Disruptions to Laboratory Life Study

This page shares findings from the Disruptions to Laboratory Life (DLL) study, a research project I launched in August 2020. Continue reading to learn more about the project and laboratory workers' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings have also been published in Science, Technology, & Human Values.

ABOUT THE DLL PROJECT

This study began with a simple question: how was laboratory life changing in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic? As an ethnographer who has spent much time in lab settings observing the mundane aspects of bench work in my research, I was familiar with the hustle and bustle of lab life: shared equipment in packed space, lab mates running from room to room, rigid experimental protocols, and informal chit chat with passersby and lab mates. How could lab work continue, when the key recommendations to slow the spread of COVID-19 were to avoid close contact with others in indoor settings - something nearly impossible to do in most lab settings? What did "doing science" look like during this time of extraordinary upheaval?

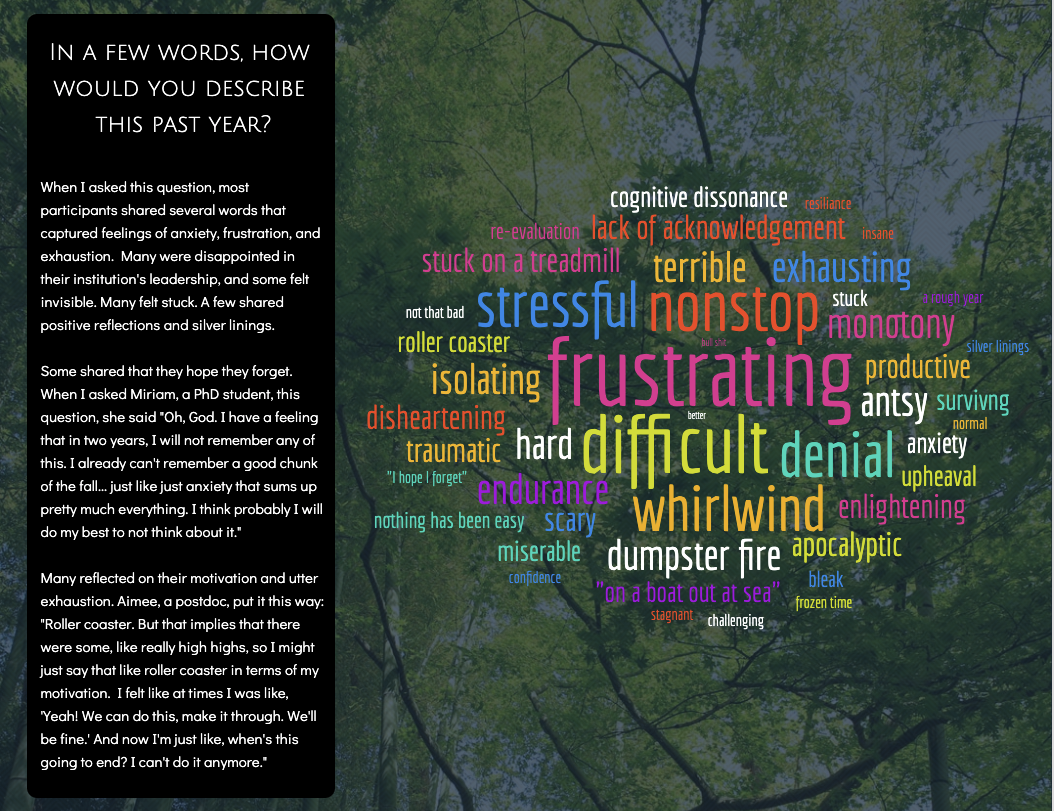

I wanted to understand how practices were changing in response to the pandemic, what sorts of disruptions were impacting scientific work, and what this experience was like for people working in academic laboratories. In a time when biomedical science was in the spotlight to develop COVID-19 therapies and vaccines, the often invisible and taken for granted parts of scientific work seemed important to capture. The DLL project draws on interviews with 39 trainees (postdocs and advanced doctoral students) in a range of biomedical fields and institutions across the US. Findings from this project elucidate how the pandemic not only disrupted their scientific work and personal lives, but also made visible power dynamics and inequality in the lab environment. This page shares the experience of workers in their own words.

PRELIMINARY FINDINGS

LOSS OF SOCIAL LIFE * INSUFFICIENT SUPPORT & LEADERSHIP * PRESSURES TO PRODUCE * LOSS OF MOTIVATION & JOY

LOSS OF SOCIAL LIFE

Overwhelmingly, what participants missed most were the social aspects of their work. The informal conversations that helped to spur new ideas, discussing failures over coffee or happy hour, and routine social interaction were key features of lab work that made it enjoyable, and had clear benefits for their work. Because labs needed to restrict capacity, the number of workers in a lab at any given time was a fraction of what it would be in normal times. When many labs reopened in summer 2020, capacity was capped at 12.5% (this increased over time).

To the right, participants explain why the social aspects of lab are so important to their experiences conducting scientific work.

The social aspect of science is almost completely gone. So then it's not as like stimulating as it used to be. You can't just like pop in and talk to people about project ideas. Yeah. I mean, I think everybody feels now that they're like completely alone, which is--well I don't think as a particularly great way to do science. Yeah. So this interaction, not even just shooting the sh*t with people, but really talking about work and science is just almost completely gone.

Olga, Postdoc

Planning lab has been a lot stricter, and essentially it means you go in [to work] and you leave. So for us, we're very social lab. We like to check in on each other and that kind of stuff. It's weird when like someone's in the adjacent room and you're in this room, and you don't have to ability to be like 'Hey!' or anything. I think it's really sad, but at the same time, like we're all trying to make, make it through with that and kind of still be able to do what we need to do and make some sort of progress.

Juliana, PhD student

I think the hardest about not being there together is just the lack of knowledge it's like in the air, maybe the best thing to say about it. Now that we're working in kind of more consistent shifts that are people around that, you know, that I do ask questions sometimes. But the one thing that I miss a lot is that the lab would have lunch together, you know, and half the time we'd talk about movies or whatnot, but things come up. It's like, 'Hey, I have this cloning problem.' 'This isn't working and I don't understand it.' Or, 'I read this thing in a paper. What do you all think?' Just like those kinds of things that come up. Even though I really tried to stay connected, it's just not the same.

Rachel, Postdoc

They have virtual talks now, but those are a lot harder for me to pay

attention and really feel engaged. Before COVID, every Friday they would have talks from trainees with pizza and then there would be a beer hour afterwards. Those were

really, really nice social things where a lot of indirect scientific

progress was made. A lot of collaborations would start there. I really miss that informal aspect

Eric, Postdoc

SUPPORT & LEADERSHIP

Many participants shared their frustrations with leadership in their labs while working through the pandemic. Given that so much of the research bench scientists conduct must be done in lab settings, in order for scientific work to continue, trainees needed to go into lab. Early on in the pandemic, some reported that they were expected to continue going into lab to finish priority experiments. The uncertainty that surrounded the weeks before institutions shut down resulted in a range of decisions: should new experiments be started? Should ongoing experiments be truncated?

Hearing about colleagues elsewhere who were told not to come in unless absolutely necessary, Isabel, a postdoc, explained that she was becoming concerned about going into the lab. She approached her PI about this. She explained that she was met with resistance, saying: "I remember having an exchange with my PI that really bothered me in which he wrote, 'well, your work is hands on.'" Others were assigned, or voluntold, that they were part of their lab's skeleton crew assigned to handle animal care. While some PIs explicitly asked workers if they were comfortable, many participants in this study explained that they were never asked and felt uncomfortable speaking out about this discomfort. Many felt like the unspoken assumption was that everyone in their lab had the same priorities and desired to continue going into lab, despite the risks. Thus participants would often adjust their schedules so that they felt safer going in. For some, like Nisha, a PhD student, this meant going into lab around 6am each day so that she could avoid other essential workers in the lab space. For others, it meant picking up weekend shifts or working late at night.

The nature of experimental work raised the question of what work could be done at home? And what were the expectations around productivity? Sure, there was always some data analysis or reading to be done, but that could only last so long. Some participants reported that their PIs implemented new accountability mechanisms during the pandemic. Spreadsheets to track ongoing projects were set up, and many participants reported that meetings with their PIs increased during the pandemic. This heightened surveillance corresponded with increased pressure to produce. As Aimee, a postdoc, described it,

Our boss wanted our plans, basically, if we were working from home. But this was a false choice. It was like, if you don't feel comfortable going in, that's perfectly fine. You can work at home, coordinate with me on what you can work on. We'll figure out how to make good use of your time or something like that. But none of us have a computational component or like that sort of thing that can be done at home. So if you're at home, you're not generating much data... you might be analyzing data, but it's not self-sustaining.

The lack of explicit discussions about expectations, coupled with the lack of acknowledgement of the social upheaval of 2020-2021 (including but not limited to: the pandemic, police murders, racial justice reckoning, record wildfires on the west coast directly impacting many participants of this study, a contentious national election, and Capitol insurrection) on personal lives and mental health, resulted in many participants feeling unsupported by their PIs and institutions. Trainees often noted that they felt the liminal nature of their positions as students and trainees, rather than employees per se, contributed to these problems.

PRESSURE TO PRODUCE

Participants reported feeling an immense pressure to produce, both internally and from their principal investigators (PIs) -- this pressure, of course, is not new. Academic science is about conducting experiments, producing data, and publishing papers. But the COVID pandemic presented new challenges: how do people keep working amidst the chaos that transpired in 2020? The distance between science and the social world weighed heavily on many of the participants in this study. Participants felt that expectations around productivity were unrealistic alongside the reality of decreased time in lab (directly resulting in less time to do experiments which yield data), supply chain issues, and their own capacity to focus. I often asked participants if they felt comfortable talking to their PIs about their expectations, and why it was so challenging to have this conversations with their boss. Heidi put it bluntly, when she said "I don't know, but it seems totally unimaginable."

In the lab, many felt they needed and were expected to produce data at the same rates as they were pre-pandemic, even though their lab time was considerably restricted due to shift schedules, and their capacity to do challenging intellectual work was fried. This pressure, for many, resulted in immense fatigue. When I conducted second round interviews, the exhaustion was palpable. Participants were tired, anxious, and frustrated. For many, this pressure to produce highlighted bigger problems with the structure and culture of academic science. Though it was made visible through pandemic routines, this pressure was not new.

To the right, participants express their frustrations with the structure of academic science and misalignments between PI and trainee goals.

It was surprising that the university administration was not more supportive of like students and post-docs working from home. I mean, certainly they let us at the beginning of the pandemic, but at a certain point it was like, 'okay, you can go back into lab.' I can understand from their perspective because the grant funding agencies have not really added any additional years onto their funding. Time is still ticking for them. My PI, for instance, is junior. So he's got the tenure clock running for him and they did extend that by one year. Given everything that's happened, you almost need more than that. I think like the higher administration level mechanisms that are in place, particularly for funding, have made it hard for the PIs to then feel okay with no productivity happening in their lab. And so as a result, there's continued pressure for students and postdocs to keep coming in and to keep working.

Helen, Postdoc

To be honest, I still feel pretty frustrated at the like environment of my lab, but not even just my lab...the culture of data comes first over like everything, like literally everything, even the health of the people doing this work. That's a bit frustrating and I feel like my PI, she tries her best in the way that she knows how to be understanding and to accommodate, but I feel like it only goes so far. So, I feel like the work is like... I'm doing the best that I can, but I still feel like the expectations are unreasonable.

Nico, PhD student

You know, my PI is a very kind man, but we are expected to persist like nothing's happened. So regardless of it, and this is the thing yeah. With top tier institutions, like my science is my life and I will endanger myself essentially for it. 'Oh, I have experiments to do, Oh, I don't feel as comfortable in work. Oh, I have to bike at midnight.' Like I will do it. Like I will be there. I have to get this stuff done. I have weekly meetings with my boss. He says, 'what have you done?' And I got to have something to show him. Not because there's any consequences. Again, if I said I'm having a really hard time, he would totally understand, but there's that internal pressure that I'm like, I need to get my work done.

Ronnie, PhD student

LOSS OF MOTIVATION & JOY

The combination of stress, pressure, and ongoing events led many participants to reflect on their identity as scientists, question where their motivation had gone, and figure out new ways keep forging ahead.

For many, they just hoped these feelings would pass -- but the longterm uncertainty presented challenges. Lane, a postdoc who has started in their new lab during the pandemic explained,

I am just overwhelmed with pandemic. You know, I moved here in April and so I don't know anyone and I don't feel like I have a support network. And I feel like what I really missed from my PhD lab was having postdocs and grad students that I was like really good friends with. If I was having an overwhelming day, they would just be like, "calm down. Like you don't have to do this." Or like, "Your boss is overreacting. Don't listen to him, he's having a bad day." I feel like those kinds of support and extras don't exist anymore and it's making me be like so much more anxious about my work. So I'm anxious about work and I'm anxious about the pandemic and I just feel like I'm not getting as much done anymore. I'm just so stressed that I'm like getting what I need to do done. But I don't feel like I have a lot of extra mental bandwidth to be excited about my work and wanting to learn new things and talk about science. And I don't know, I feel very guilty about it.

The underlying, chronic uncertainty and its accompanying anxiety posed a daily challenge for many participants in this study. Yes, the pandemic and its impacts had thrown daily life and work practices into chaos, but it was also triggering bigger impacts. Universities and research institutions across the US instituted hiring freezes. Many labs opted not to take on new postdocs in order to conserve resources. In other words, the scientific futures that participants had imagined for themselves, began to feel less certain. What will hiring look like in the next few years? Will there be a huge backlog of highly qualified candidates to compete with? Many became acutely aware of the tradeoffs, like James, a postdoc, who explained: "I've been interested in being an academic PI for a long time. I think I have the characteristics to be a good PI, and I'm settled on that. But I also am keenly aware that my decision to continue to pursue this academic track comes at a cost. It comes at a cost of, frankly, my emotional wellbeing. Like staying in a place with the stress of COVID plus the uncertainty of trying to find a home run project after failures previously. There's certainly a cost from an emotional standpoint on that side of things. And then of course there's a financial cost associated with it as well."

Alongside looming future concerns, participants were feeling a loss of joy in their work. Isabel, a postdoc, explained that this loss of motivation and creativity was crushing because it was an extreme source of joy for her in her career.

I just keep telling myself that things will be better in the spring. If they're not then I could deal with it then, right? What is been really hard is I loved going there before. Of course, there's bad stuff and I complained about it. And every once in a while it got really hard and it would be nice to take a vacation, but work was like a source of extreme joy to be there with like colleagues who I enjoyed interacting with, just to feel comfortable and safe. And to feel like I could be creative and I wanted to do extra stuff if I felt like it, and now there's absolutely none of that. It has disappeared. So it's like the loss of that. When I go, initially I was trying to find that and I just can't find it.

The loss of joy, coupled with the increased uncertainty and new realities of scientific work, led many participants to question their satisfaction with science and the ways in which their identity was so wrapped up in their professional lives.

DLL STUDY METHODS & DESIGN

STUDY DESIGN

The DLL study is an interview based qualitative study that utilizes grounded theory methodology. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews with biomedical research trainees (advanced doctoral students and postdocs) who spend 70% or more of their pre-pandemic work time at the bench, over an eight month time period. Initial interviews (T1) were conducted in September-October 2020 (n=39), approximately six months into the pandemic. Follow up interviews (T2) were conducted in February-March 2021 (n=36), approximately six months following each participant's first interview. This second time point was approximately one year after early cases of COVID-19 were reported in the United States, and 11 months following widespread shutdowns. All transcripts were transcribed for analysis and identifying details were scrubbed. All names are pseudonyms.

Who participated in this study?

Biomedical trainees (n=39) were completing their training at a range of eight universities and research institutes with high research activity in the United States (R1 institutions). Trainees included postdocs and advanced PhD students in a range of biomedical science fields including neuroscience, microbiology, immunology, bioengineering, chemical biology, among other interdisciplinary biomedical sciences. Participant characteristics are detailed below.